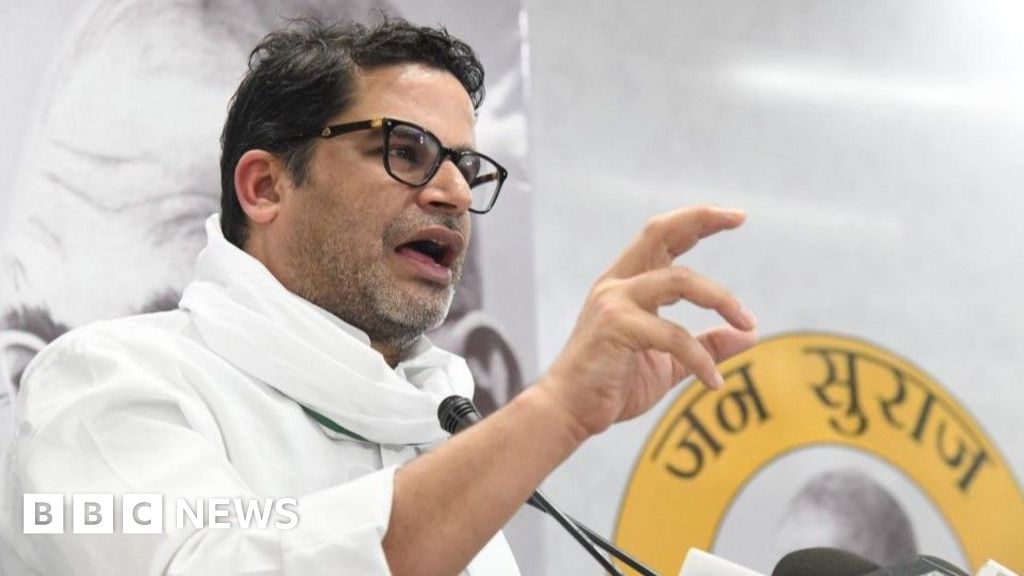

For more than a decade, Prashant Kishor was the quintessential behind-the-scenes strategist in Indian politics. Known for his data-driven approach and keen political acumen, Kishor earned the trust of some of India’s most powerful leaders, including Prime Minister Narendra Modi and influential regional figures like Nitish Kumar of Bihar and Mamata Banerjee of West Bengal. He was the political tactician who shaped campaigns, diagnosed voter behavior, and engineered electoral victories, all from the shadows. Yet, when Kishor decided to step out of the wings and into the spotlight himself by launching his own political party, Jan Suraaj (meaning "People’s Good Governance"), the results were unexpectedly stark. His carefully crafted strategy, which worked wonders for others, faltered dramatically when tested at the ballot box.

Jan Suraaj was launched with much fanfare and ambition in Bihar, India’s third most populous state and one of its poorest. Kishor promised a break from the entrenched cycle of caste-based patronage politics and long-standing stagnation. Over two years, he traversed the length and breadth of the state, building a slick organizational structure, fielding candidates in nearly all 243 assembly seats, and generating significant media buzz. Yet, despite the hype and Kishor’s personal charisma, Jan Suraaj failed to secure a single seat and garnered only a tiny fraction of the votes. Meanwhile, the incumbent alliance led by Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) swept the elections decisively.

This outcome exposed a fundamental truth about Indian politics: visibility and media attention do not necessarily translate into electoral success. In a political landscape as complex and deeply rooted as Bihar’s, breaking into the system from the outside—no matter how innovative or well-funded—is far more difficult than diagnosing its flaws or managing others’ campaigns. Kishor’s experience serves as a cautionary tale about the limits of strategy without a solid grassroots base and the importance of emotional connection with voters.

The political history of India offers many lessons in this regard. Since the emergence of the Telugu Desam Party (TDP) in 1983, very few new parties have managed to become significant players in the political arena. Those that have, such as West Bengal’s Trinamool Congress or Odisha’s Biju Janata Dal, were typically breakaway factions of larger parties with established social bases and networks. Others, like Assam’s Asom Gana Parishad (AGP) or Delhi’s Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), rose rapidly thanks to mass mobilizations and political crises—moments of intense public anger or demand for change.

Jan Suraaj, in contrast, was neither a product of grassroots agitation nor born out of a palpable anti-incumbency wave. Bihar’s political climate in 2025 was surprisingly stable, with voters largely adhering to existing political and social loyalties. Rahul Verma, a political scientist, notes that without a visible crisis or widespread dissatisfaction, Kishor’s party struggled to appear as a credible alternative despite the hard work and organizational efforts.

Unlike parties such as the AGP, TDP, or the AAP—which emerged from socio-political movements with deep emotional and grassroots resonance—Jan Suraaj was conceived more as an intellectual and strategic project. Saurabh Raj, a scholar at the Indian School of Democracy, describes it as a “designed political start-up,” created to fill what Kishor identified as a “political vacuum.” Attempting to transform this intellectual ideal into a mass movement, Kishor undertook a lengthy padayatra (foot march) across Bihar to connect with voters. Yet, the party lacked the organic, movement-based energy that typically fuels new political forces. It was more an engineered campaign than a spontaneous uprising.

Kishor’s approach emphasized governance reforms, job creation, and addressing forced migration—issues highly relevant to Bihar’s population, which is predominantly young. He sought to break away from the entrenched caste and patronage politics that have long dominated the state. His campaign was marked by modern techniques, including data analytics, charismatic messaging, and even the use of memes to appeal to younger voters. However, despite this modernity and innovative style, many analysts believe Jan Suraaj lacked the emotional intensity and grassroots loyalty that drive insurgent political movements.

One key factor that may have undermined the party’s appeal was Kishor’s own decision not to contest an assembly seat. This choice arguably diminished the party’s credibility