In February 1953, two scientists, James Watson and Francis Crick, walked into a pub in Cambridge and proclaimed they had discovered "the secret of life." This was no mere boast; their groundbreaking revelation was the identification of the structure and function of deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA. This discovery stands among the most significant in the history of modern science, comparable to the foundational work of Gregor Mendel in genetics and Charles Darwin in evolution. The profound implications of their work unfolded over subsequent decades, transforming biology and medicine and opening the door to revolutionary advances as well as difficult ethical questions.

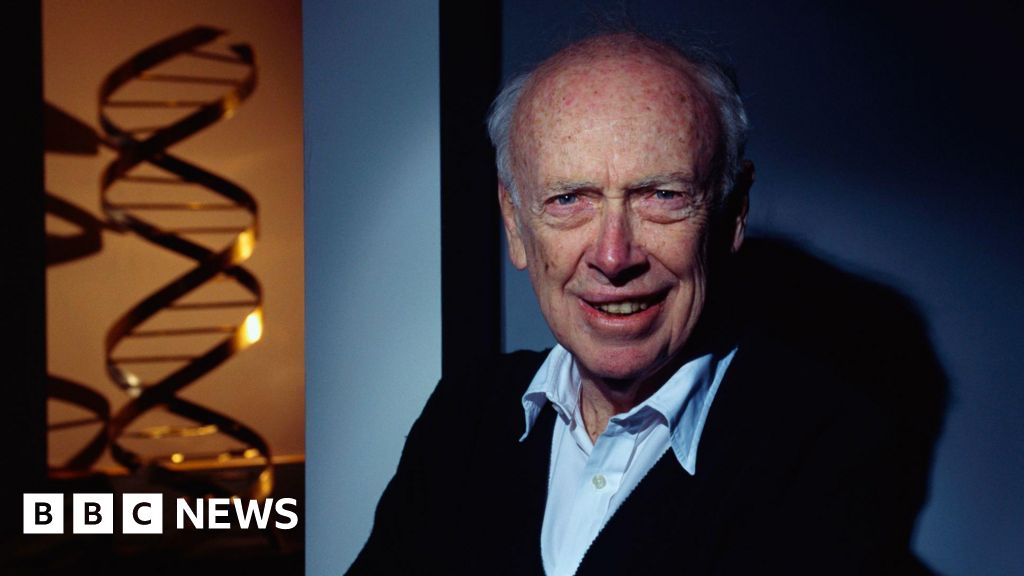

Watson, an American biologist working at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, and Crick, a British physicist, deciphered that DNA is shaped as a three-dimensional double helix — a twisting ladder-like structure. This insight unlocked the understanding of how genetic information is stored, replicated, and passed from one generation to the next. Watson famously said that when they realized the answer, they had to "pinch ourselves" because the solution was so elegant and beautiful. Their discovery earned them, along with Maurice Wilkins, the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1962 and secured their place among the greatest scientific minds.

However, the story behind the discovery was complex and sometimes contentious. Watson and Crick’s work was deeply intertwined with that of other scientists, particularly Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin at King’s College London. Franklin was an expert in X-ray diffraction and produced critical photographs, especially the famous “Photo 51,” which provided essential evidence of DNA’s helical structure. While Wilkins collaborated more amicably with Watson and Crick, Franklin was known to be guarded and worked independently, leading to strained relations. Watson and Crick’s access to Franklin’s data, sometimes without her direct permission, has sparked ethical debates about scientific credit. Franklin’s early death from ovarian cancer at age 37 meant she was never recognized with the Nobel Prize, a fact many consider a grave injustice.

Watson’s life and career extended well beyond the DNA discovery, but his legacy remains complicated by his controversial public statements and behavior. Born in Chicago in 1928, James Dewey Watson was raised in a family that valued science, politics, and critical thinking. His father, a scientist and bird-watcher, instilled in him a love for nature and observation, while his mother was active in Democratic politics. Watson described himself as an “escapee” from the Catholic faith in which he was raised, influenced by his father’s skepticism. Despite early academic struggles and social awkwardness, he earned a scholarship to the University of Chicago at just 15.

Initially interested in ornithology, Watson shifted his focus to genetics after reading Erwin Schrödinger’s book *What is Life?* At Cambridge, his partnership with Crick flourished as they built physical models to solve the puzzle of DNA’s structure. Their race against Wilkins and Franklin was marked by scientific rivalry and interpersonal conflicts, but ultimately their combined efforts propelled the discovery forward.

Following the Nobel Prize, Watson moved to prestigious academic positions, including Harvard University and later the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York. At Cold Spring Harbor, he revitalized the institution into a leading center for genetic research. In 1968, Watson published *The Double Helix*, a candid memoir that revealed the personalities, struggles, and controversies behind the DNA discovery. The book was both celebrated for its honesty and criticized for its dismissive and sometimes offensive portrayal of colleagues, especially Rosalind Franklin.

Despite his scientific brilliance, Watson’s public image was often overshadowed by his provocative and sometimes offensive remarks. He made headlines for speculating on a link between race and intelligence, particularly suggesting that black people were less intelligent than white people — views widely denounced as racist and scientifically unfounded. Such statements led to severe professional consequences: the London Science Museum canceled his lecture, and Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory stripped him of executive roles, relegating him to a ceremonial position.

Watson also stirred controversy with comments about employment discrimination, beauty, and genetics, as well as his views on abortion related to the sexual orientation of unborn children. He defended these opinions as advocating for choice and genetic understanding, but many found them ethically troubling and socially insensitive. His autobiography *Avoid Boring People* included harsh criticisms of fellow academics, whom he labeled as “dinosaurs,” “deadbeats,” and “has-beens,” alienating colleagues and peers