On November 20, 2025, Scientific American published an insightful exploration into the microscopic wonders of nature through the lens of artist and writer Michael Benson’s latest book, *Nanocosmos: Journeys in Electron Space*. The book showcases breathtaking images of snowflakes, radiolarians, diatoms, dinoflagellates, lunar rocks, and other tiny natural wonders, all captured with the help of a scanning electron microscope (SEM). Benson’s unique approach blends art and science, revealing the intricate beauty and complexity of the natural world at scales invisible to the naked eye.

Michael Benson is no stranger to the cosmos; his previous works, such as *Planetfall* and *Cosmigraphics*, focused on vast cosmic landscapes and humanity’s place in the universe. However, for *Nanocosmos*, Benson turned inward, spending seven years in a small laboratory in Canada examining the minuscule. This shift from the macro to the micro is not just about scale but about exploring space and time in a different dimension. Benson likens this microscopic world to the cosmos, reflecting on a famous quote by futurist Buckminster Fuller who, when asked if it bothered him not to have been to space despite his work on space colonization, replied, “My God, man, where do you think we are?” In essence, Benson’s work continues the exploration of our position in space—only now at the submillimeter scale.

One of the major technical challenges Benson faced was photographing snowflakes. Snowflakes are famously unique and delicate, but capturing them through an electron microscope is particularly difficult because ice sublimates quickly in a vacuum and is sensitive to the electron beam. To overcome this, Benson devised a method using liquid nitrogen and a cryopod—an apparatus originally designed to transport DNA samples—to keep snowflakes frozen at extremely low temperatures (around -200 degrees Celsius). This technique allowed him about three minutes to capture each snowflake’s detailed structure before it melted or sublimated. The resulting images reveal snowflakes’ astonishing complexity and individuality, even highlighting imperfections that Benson came to appreciate as part of their natural beauty.

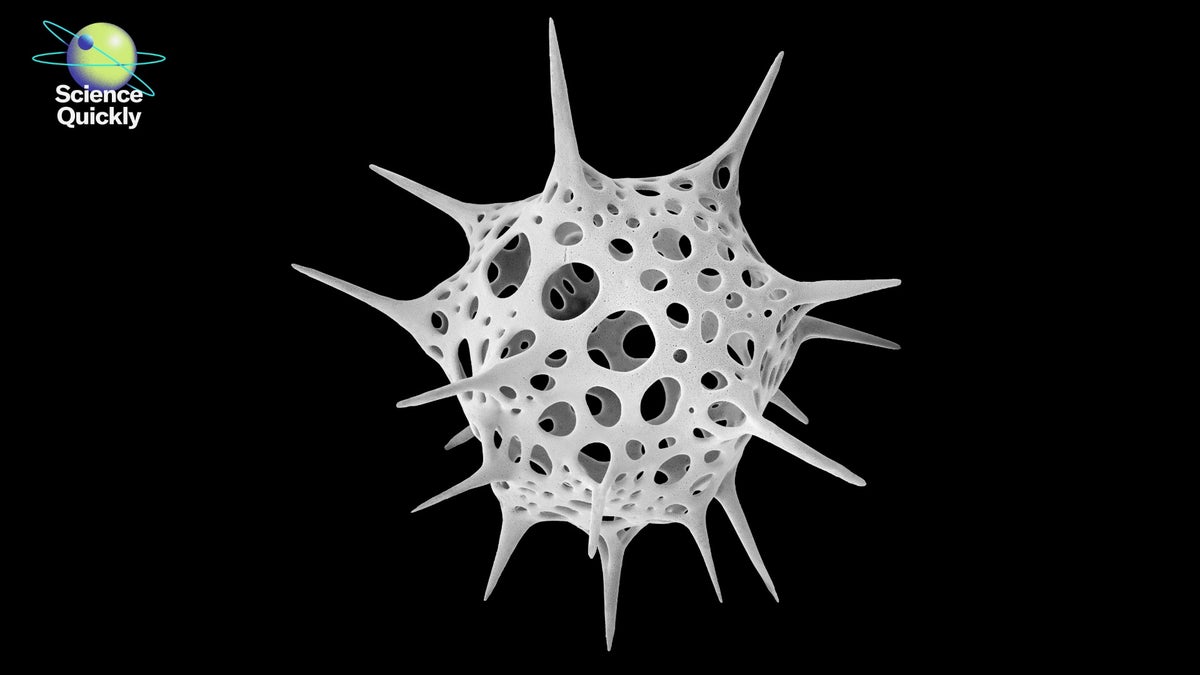

Beyond snowflakes, Benson’s book features stunning images of radiolarians, microscopic single-celled marine organisms with exquisite silica skeletons. These creatures, invisible to the naked eye, take on a glass-like quality under the SEM, exhibiting intricate latticework and spiny projections that aid their flotation in the ocean. Radiolarians have fascinated scientists and artists alike for centuries, notably inspiring the 19th-century German biologist Ernst Haeckel, whose illustrated book *Art Forms in Nature* brought these microscopic marvels into public view long before electron microscopes existed. Benson’s images reveal these organisms with extraordinary clarity, showing details that Haeckel could only dream of capturing.

The book also delves into diatoms and dinoflagellates, other microscopic single-celled organisms critical to Earth’s ecosystems. Diatoms produce a significant portion of the oxygen in our atmosphere and construct glassy silica shells that serve as protective “petri dishes” housing symbiotic algae. Benson’s images reveal their sleek, geometric beauty and complex surface textures, which sometimes resemble Islamic architecture or delicate lacework. Dinoflagellates, on the other hand, sport unique features like flagella that enable them to spin and propel themselves through the water, adding a dynamic and almost mechanical aspect to their forms. These organisms demonstrate the incredible complexity and evolutionary sophistication of even the smallest forms of life, challenging the notion that single-celled life is simple.

Another fascinating subject in *Nanocosmos* is lunar impact glass collected during the Apollo 16 mission. These tiny fragments, formed from molten rock blasted off the moon’s surface by meteorite impacts millions of years ago, look remarkably like miniature mountain ranges or rugged geological landscapes when viewed up close. The images capture fracturing, weathering, and micrometeorite impacts that have scarred the glass over eons of exposure to space. Benson was careful not to damage or alter these priceless samples: unlike most specimens scanned under the electron microscope, which are coated with a thin layer of conductive material to prevent charging, the lunar samples had to be imaged without such treatment. The resulting photographs offer viewers a chance to explore extraterrestrial landscapes on an intimate, tactile scale.

Benson’s work is not just scientific documentation but a form of art. Unlike scientific imagery, which prioritizes empirical data and research, Benson approaches his SEM images as