**The Slop Cycle: How Every Media Revolution Breeds Both Rubbish and Art**

The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) has brought with it a flood of new content, much of which has been derided as low-quality or meaningless filler—what some have come to call “slop.” This term, popularized in the context of AI-generated output, echoes a long-standing pattern in cultural history: whenever new technologies enable mass production of media, there is an initial surge of crude, derivative, or outright poor material. Yet within this overwhelming tide of quantity over quality, valuable new forms of artistic expression and innovation often emerge. Understanding this cycle is crucial as society navigates the challenges and opportunities presented by AI and the content it generates.

The term “slop” as a descriptor of AI content was popularized around 2024 by a poet and technologist known as “deepfates,” who used it specifically to refer to unwanted or mindlessly generated AI output. Developer Simon Willison further clarified that while not all AI content is “slop,” the term aptly captures content that is produced without genuine creativity and thrust upon audiences who did not request it. Today, “slop” functions as a cultural critique, often used pejoratively to dismiss AI-generated works en masse. While much AI content does indeed lack substance, an indiscriminate rejection risks overlooking the minority of AI creations that are innovative or meaningful.

This dynamic is far from new. The production of mass culture has always been messy and uneven. The biblical book of Ecclesiastes, written around 300 to 200 BCE, lamented the endless production of books, reflecting an early awareness of information overload. Throughout history, whenever new communication technologies have emerged, they have been accompanied by waves of hastily produced, derivative works intended to capture attention quickly. Yet, amid these surpluses, new artistic genres and cultural treasures have often taken shape.

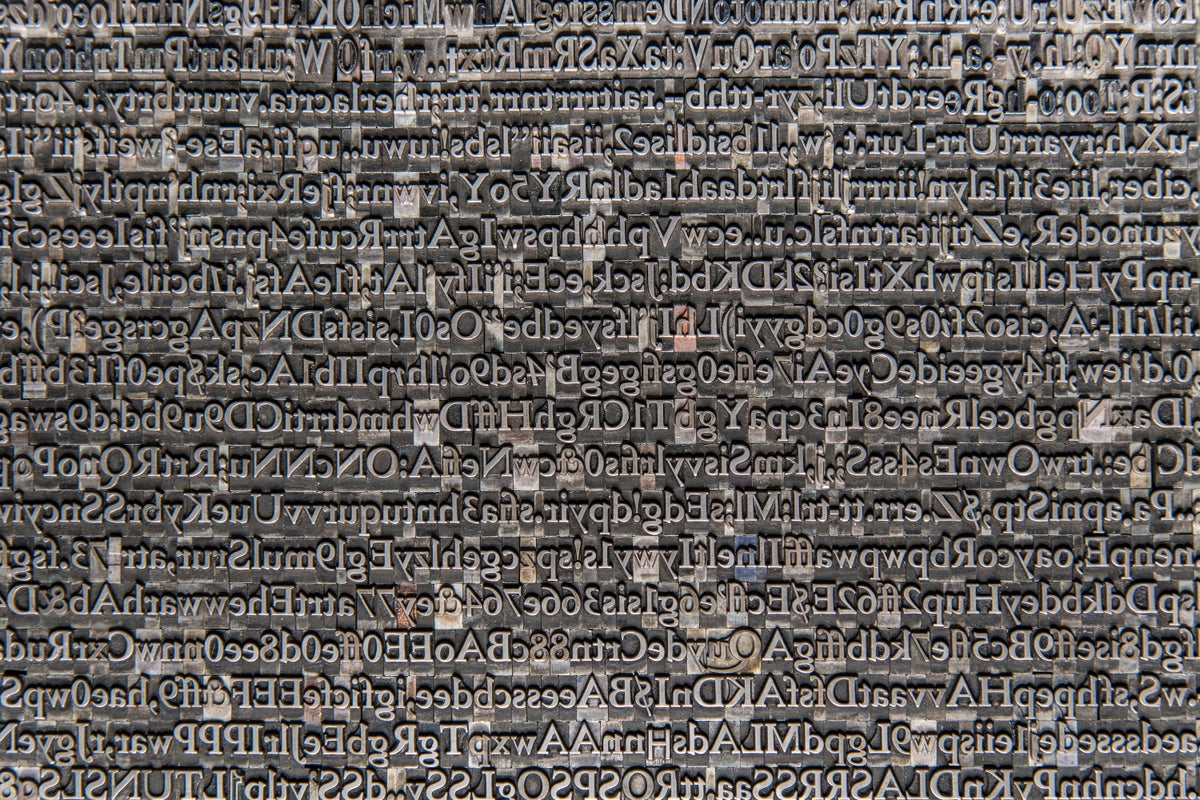

A significant historical example occurred after Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the movable-type printing press in the 1450s. Much like AI today, Gutenberg’s press revolutionized content creation by making it possible to rapidly produce cheap printed material. Over the following centuries, inexpensive chapbooks and broadside ballads became widespread in Britain. These pamphlets and ballads brought news, satire, and stories to audiences who previously had limited access to books, especially the illiterate who consumed content through oral performance. Though much of this material was trivial or lowbrow, it played an essential role in education and entertainment, influencing literary giants like William Shakespeare and Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

The 18th century saw another wave of mass-produced media with the rise of “Grub Street” in London—a hub for cheap printing and hack writing. Named after a district crowded with print shops and cheap lodgings, Grub Street became synonymous with low-quality pamphlets, satires, political tracts, sensational stories, and early forms of what we might now call “churnalism.” Critics of the time, including Samuel Johnson—who ironically made his early living within this milieu—decried Grub Street as a symbol of commercial corruption of literature. Yet, this environment also fostered the development of the first modern freelance economy and mass-print culture, producing works by notable authors such as Daniel Defoe, Eliza Haywood, and Jonathan Swift.

The 20th century’s cinema boom followed a similar trajectory. By 1908, thousands of nickelodeons—five-cent storefront theaters—were showing films nonstop, demanding rapid production of movies. This glut of content included a substantial amount of low-quality films, or “B-movies,” many of which were quickly forgotten. However, the industry infrastructure built during this period helped spread information and cultural narratives, including aiding immigrants in learning English. Moreover, these productions served as training grounds for filmmakers and actors who would later shape Hollywood’s golden age, including Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Jack Nicholson, and Robert De Niro.

Across these historical moments—from the printing press to Grub Street to early cinema—the pattern is clear: new technologies lower the barriers to content creation, flooding the market with quickly produced material that is often derivative or low-quality. Yet, this democratization also widens the pool of creators and participants, enabling new voices and forms of art to emerge over time. The mass production of culture may yield much forgettable content, but it also produces the conditions for innovation and originality to flourish