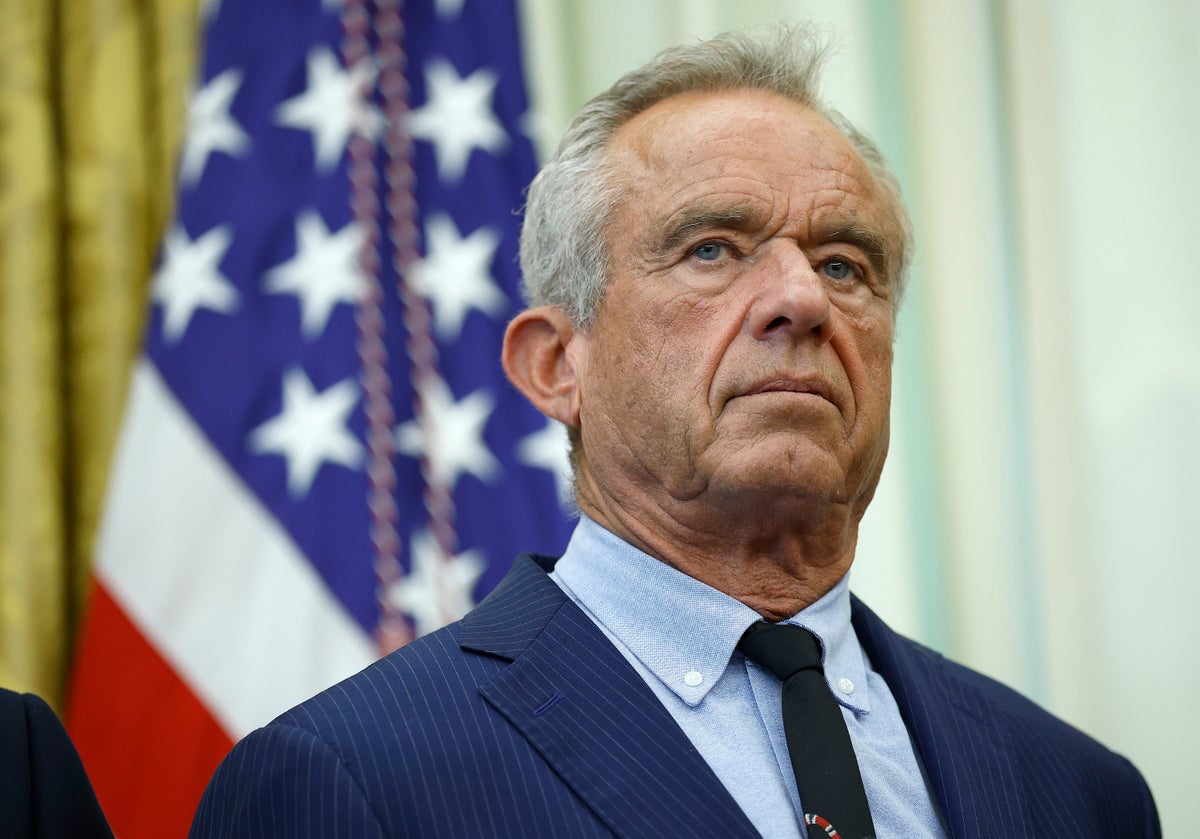

A comprehensive new study published in Science Advances has found no evidence that exposure to recommended levels of fluoride in drinking water negatively affects children’s cognitive development or intelligence. This research challenges claims made by U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., who argued that fluoridating tap water could harm brain development. The study offers strong U.S.-based evidence supporting the safety of community water fluoridation, a public health measure that has been under scrutiny in recent years.

Fluoride has been added to public water supplies in the United States since 1945, starting in Grand Rapids, Michigan, as a measure to prevent tooth decay, which remains one of the most common chronic childhood diseases. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) hailed water fluoridation in 1999 as one of the greatest public health achievements of the 20th century. Today, more than 62% of the U.S. population receives fluoridated water, typically maintained at about 0.7 milligrams of fluoride per liter. Despite its long-standing use, the practice has faced growing opposition, with several states and cities reconsidering or outright banning fluoride in their water systems due to concerns about potential cognitive harms.

The new study, led by University of Minnesota sociologist John Robert Warren and his colleagues, offers a robust examination of fluoride’s effects on cognitive outcomes by analyzing decades of data. The researchers utilized information from the High School and Beyond study cohort, which was conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics and tracked thousands of Americans from 1980 through 2021. Initially, the study included 26,820 participants, approximately half of whom participated in follow-ups decades later.

Warren’s team estimated each participant’s fluoride exposure from conception through the 12th grade by correlating residential information with data on local water fluoridation levels. They then compared these exposure estimates with participants’ academic performance during high school—measured by standardized tests in reading, math, and vocabulary—as well as cognitive assessments in later adulthood, including memory tests administered when participants were in their 60s.

The findings were clear and reassuring. Children who consumed recommended levels of fluoride during their upbringing performed slightly better on all academic measures in high school compared to those who had insufficient fluoride exposure. Importantly, in adulthood, no adverse differences were observed in memory, attention, or other cognitive functions between those exposed to fluoridated water and their peers without sufficient exposure. These results suggest that fluoride at recommended levels does not impair cognitive abilities and may even be linked to marginally improved academic outcomes.

While the study did not directly investigate why fluoride exposure correlated with better school test scores, Warren hypothesized that improved dental health—thanks to fluoride’s protective effects against tooth decay—could reduce school absences due to illness or dental pain, thereby enhancing learning opportunities. Pediatrician Susan Fisher-Owens, who was not involved in the research, echoed this view, noting that healthier children are more likely to attend school consistently and perform better academically. She also emphasized that this study is a valuable addition to the broader literature affirming the safety and benefits of water fluoridation, particularly because it uses U.S. data, which strengthens its relevance for policy decisions in the country.

Despite its strengths, Warren acknowledged the study’s limitations. The research relied on standardized test scores rather than direct IQ measurements, which are a more precise indicator of cognitive ability. However, his team is preparing to publish additional research based on IQ tests administered to another cohort followed since the 1950s, which should provide further insight into the relationship between fluoride exposure and intelligence.

The timing of this research is significant, as debates over fluoridation policies have intensified nationwide. In 2025, Utah and Florida implemented bans on fluoride in public drinking water, reflecting growing public concern influenced in part by claims linking fluoride to cognitive harm. Epidemiologist David Savitz, who was not involved in the study, stressed that any policy evaluation must weigh both the benefits and potential risks of fluoridation. Nonetheless, he pointed out that the evidence supporting the benefits of fluoride in preventing dental decay is much stronger than the evidence suggesting any cognitive harms. “The only reason we fluoridate the water is because of the benefits. If it did not have benefits, we would not do it,” Savitz said.

This new research thus provides timely and reassuring evidence supporting the continued use of fluoride in public water supplies at recommended levels. It underscores fluoride’s role as