In recent years, wearable fitness devices like smartwatches and rings have introduced many people to a new health metric called heart rate variability (HRV). This measure, which tracks the tiny fluctuations in the time interval between consecutive heartbeats, has become a popular feature on devices such as the Oura ring and Apple Watch. While the concept of HRV might sound concerning—after all, irregular heartbeats often signal health problems—the reality is quite the opposite. A certain amount of variability in heart rate actually reflects better health and well-being, offering a window into the body’s autonomic nervous system and its ability to adapt to stress.

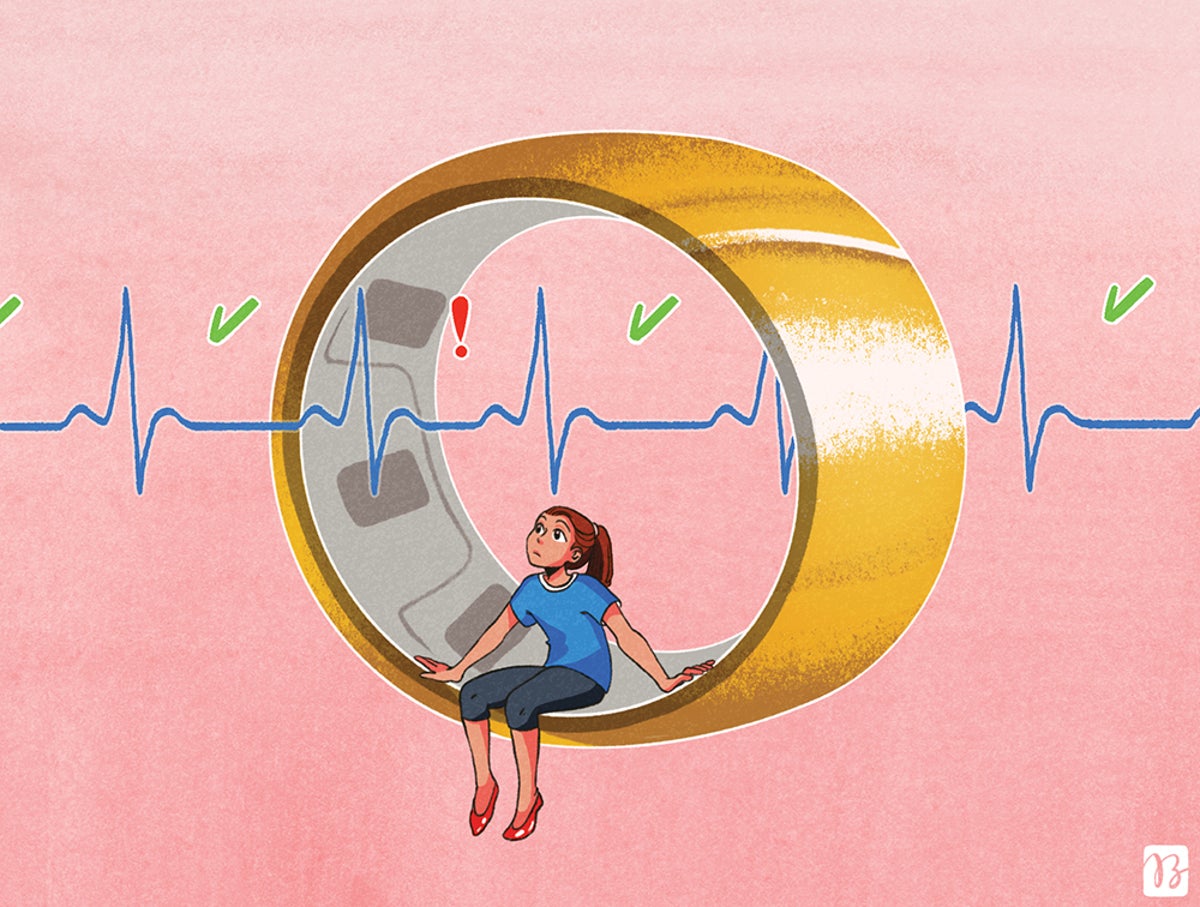

The story of how HRV entered the mainstream begins with the rise of wearable health monitors. Journalist Lydia Denworth shares her personal experience with the Oura ring, which she began using to track her sleep and activity levels. She noticed that her HRV readings were often flagged in red, signaling that she should “pay attention.” Initially confused and slightly alarmed by this warning, Denworth learned that HRV is quite different from the well-known concept of arrhythmias—dangerous irregularities in heart rhythm. Instead, HRV measures the subtle, millisecond-level variations in the time between heartbeats, which naturally fluctuate throughout the day.

Medical experts confirm that HRV is not yet a standard clinical tool, but its popularity among consumers is rapidly growing. Bryan Wilner, an electrophysiologist at the Baptist Health Miami Cardiac and Vascular Institute, notes that while HRV hasn’t been widely used in everyday medical practice, consumer interest and the availability of noninvasive monitoring devices have brought it to the forefront. This surge in interest is generating vast amounts of data, which could eventually help doctors better diagnose and treat a range of conditions, though that potential is still in the early stages.

To understand HRV, it’s important to know how the heart is regulated. The autonomic nervous system, which controls involuntary bodily functions, has two main branches that influence heart rate. The sympathetic nervous system triggers the “fight or flight” response, increasing heart rate during stress or physical activity. Conversely, the parasympathetic nervous system promotes “rest and digest” functions, slowing the heart rate down. HRV captures how these two systems interact by measuring the variation in the time intervals between heartbeats.

A high HRV generally indicates a healthy, adaptable autonomic nervous system. It suggests that the body can efficiently respond to and recover from stressors, whether physical or psychological. People with higher cardiovascular fitness tend to have higher HRV, as do younger individuals, since HRV naturally declines with age. On the other hand, a low HRV can signify reduced resilience and has been linked to stress, anxiety, poor sleep, dehydration, and certain medications. In clinical contexts, low HRV is associated with a higher risk of complications and mortality in patients recovering from heart attacks or living with heart failure.

Despite the significance of HRV, there is no universal “good” or “bad” number. Attila Roka, an electrophysiologist at the CHI Health Clinic Heart Institute, explains that normal HRV values can range widely—from about 20 to 70 milliseconds—and are highly individual. For Denworth, her HRV hovered around 14 milliseconds for several weeks, which was lower than average and prompted her device’s alerts.

The gold standard for measuring HRV remains the electrocardiogram (ECG), which records the heart’s electrical activity with high precision. Advanced cardiac devices like pacemakers and defibrillators can also monitor HRV. Physicians may use Holter monitors—portable ECG devices worn continuously for several days—to gather comprehensive data on heart rhythms and variability. In contrast, consumer wearables like the Apple Watch and Oura ring estimate HRV by detecting pulse fluctuations through optical sensors rather than directly measuring electrical signals. While the accuracy of these consumer devices is still being studied, experts emphasize that tracking trends in HRV over time is more meaningful than focusing on single readings.

One of the most promising areas of HRV research lies beyond cardiovascular health—in mental and emotional well-being. Pamela Mason, chief of cardiac electrophysiology at UVA Health, highlights that chronic stress and mental health conditions such as depression and bipolar disorder may be reflected in reduced HRV. When the nervous system is stuck in a persistent “fight or flight” mode, HRV tends to decrease, indicating less flexibility in the body’s stress response. Even among otherwise healthy