A recent clinical trial has demonstrated that an innovative electronic retinal implant can restore partial vision in people who have been rendered functionally blind by age-related macular degeneration (AMD). While not providing full sight restoration or significant quality-of-life improvements, the device marks a promising step forward in treating this widespread cause of blindness among older adults.

Age-related macular degeneration is the leading cause of incurable blindness in elderly populations worldwide. It primarily affects the central retina, where the light-sensitive photoreceptor cells—rods and cones—gradually die, leading to a loss of sharp, central vision. Individuals with advanced dry AMD, the form studied in this trial, retain peripheral vision but lose the ability to recognize faces, read, drive, or watch television due to the degeneration of their central vision. Approximately five million people globally suffer from advanced dry AMD, underscoring the urgent need for effective treatments.

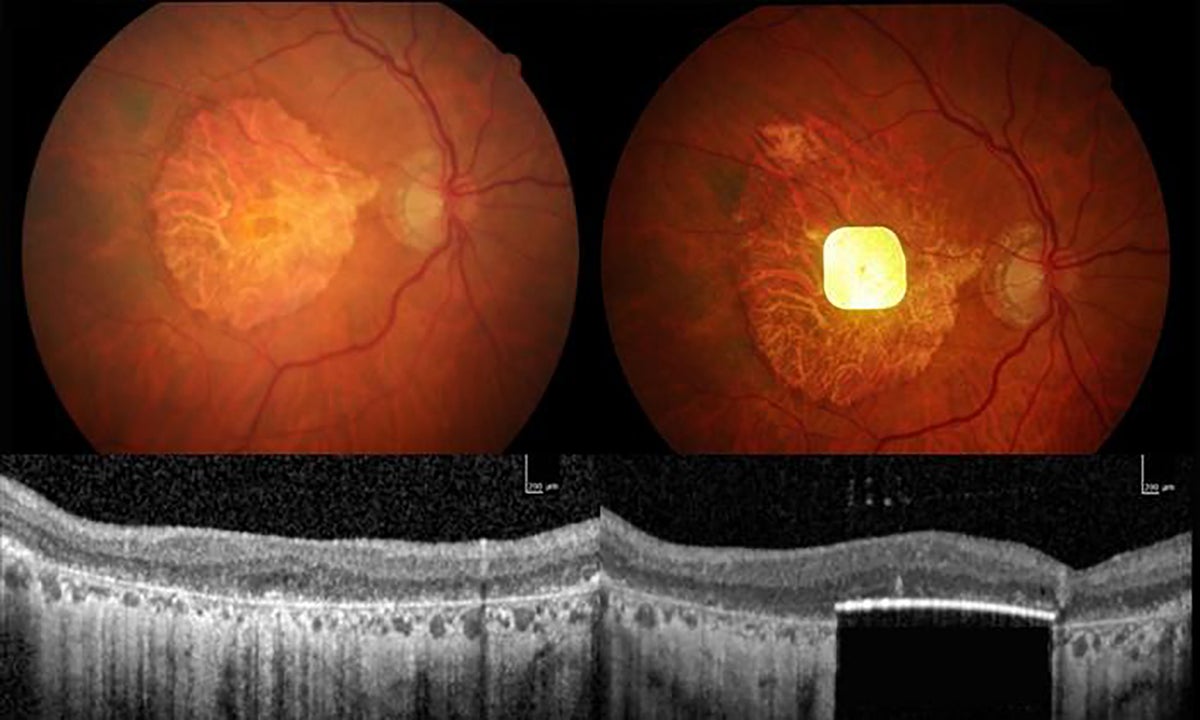

The trial, recently published in The New England Journal of Medicine, involved 38 participants from 17 clinical sites across five European countries. These individuals had severe retinal degeneration from advanced dry AMD and were implanted with a device called PRIMA — a photovoltaic retina implant microarray. The device itself is remarkably small, measuring just 2 millimeters by 2 millimeters and only 30 micrometers thick, and is surgically inserted beneath the retina to replace the lost photoreceptor cells.

Distinct from previous retinal implants, PRIMA is wireless and photovoltaic, meaning it uses incoming photons not only to detect light but also as its energy source to generate electrical stimulation. The system works in tandem with a specially designed pair of glasses equipped with a camera. The camera captures images and converts them into patterns of infrared light, which are then transmitted to the retinal implant. This stimulation activates the surviving retinal neurons, which continue to send visual information to the brain’s processing centers. The technology thereby bypasses the damaged photoreceptors and attempts to restore a functional sense of sight.

One year after implantation, results showed that 80% of the participants experienced clinically meaningful improvements in vision, with many able to read letters, words, and numbers again—a remarkable achievement given their previous level of blindness. On average, individuals improved by about two lines on a standard eye chart, a significant gain considering the severity of their vision loss. Most users reported medium to high satisfaction with the device, and many had integrated it into their daily lives for reading and other tasks.

Despite these encouraging functional improvements, the device did not translate into measurable enhancements in the participants’ overall quality of life. A questionnaire assessing daily living found no significant changes one year post-implantation. Some experts have suggested that the observed improvements in vision tests could be influenced by the participants’ motivation and the intensive training they underwent to use the device, rather than the device itself. They recommend further studies with randomized placebo-controlled groups to more definitively gauge efficacy.

The trial’s leader, ophthalmologist Frank Holz from the University of Bonn, acknowledges the device’s current limitations. The PRIMA implant contains 381 pixels, each measuring 100 micrometers square, which constrains the resolution and results in relatively slow, non-fluid reading experiences for users. Additionally, the vision it provides is currently limited to black and white, lacking color perception. Holz notes that while this first major breakthrough is a crucial starting point, future iterations of the device are expected to feature larger arrays with smaller pixels to improve visual acuity and potentially enable color vision. Physicist Daniel Palanker from Stanford University, who originally designed the device, is exploring ways to achieve these enhancements in next-generation implants.

Safety considerations were also addressed in the trial. Although some minor adverse events related to the surgical implantation occurred, the trial’s safety-monitoring board concluded that the benefits of the device outweighed the risks. This positive safety profile supported the device’s manufacturer, Science Corporation, based in San Francisco, in applying for European market certification in June 2025.

Beyond AMD, the PRIMA implant holds potential for treating other retinal conditions characterized by photoreceptor loss but preservation of other retinal neurons, such as retinitis pigmentosa. This broad applicability could make the technology a valuable tool in combating various forms of vision loss.

It is important to note that retinal implants like PRIMA are only one of several promising approaches being explored to restore sight in people with degenerative retinal diseases. Other avenues include stem-cell therapies aimed at regenerating photoreceptors, optogenetics techniques that introduce light-sensitive proteins into remaining retinal cells