**Cells Have a Crystal Trigger That Makes Them Self-Destruct When Viruses Invade**

Our immune system faces a relentless challenge: when a virus invades a cell, the cell must rapidly detect the threat and decide whether to self-destruct to prevent further infection. This decision must be swift and accurate, as premature self-destruction wastes valuable cells, while delayed action allows the virus to spread. Recent research has uncovered a remarkable mechanism within cells that enables this rapid, life-or-death choice, involving a unique form of protein crystallization that triggers cell death.

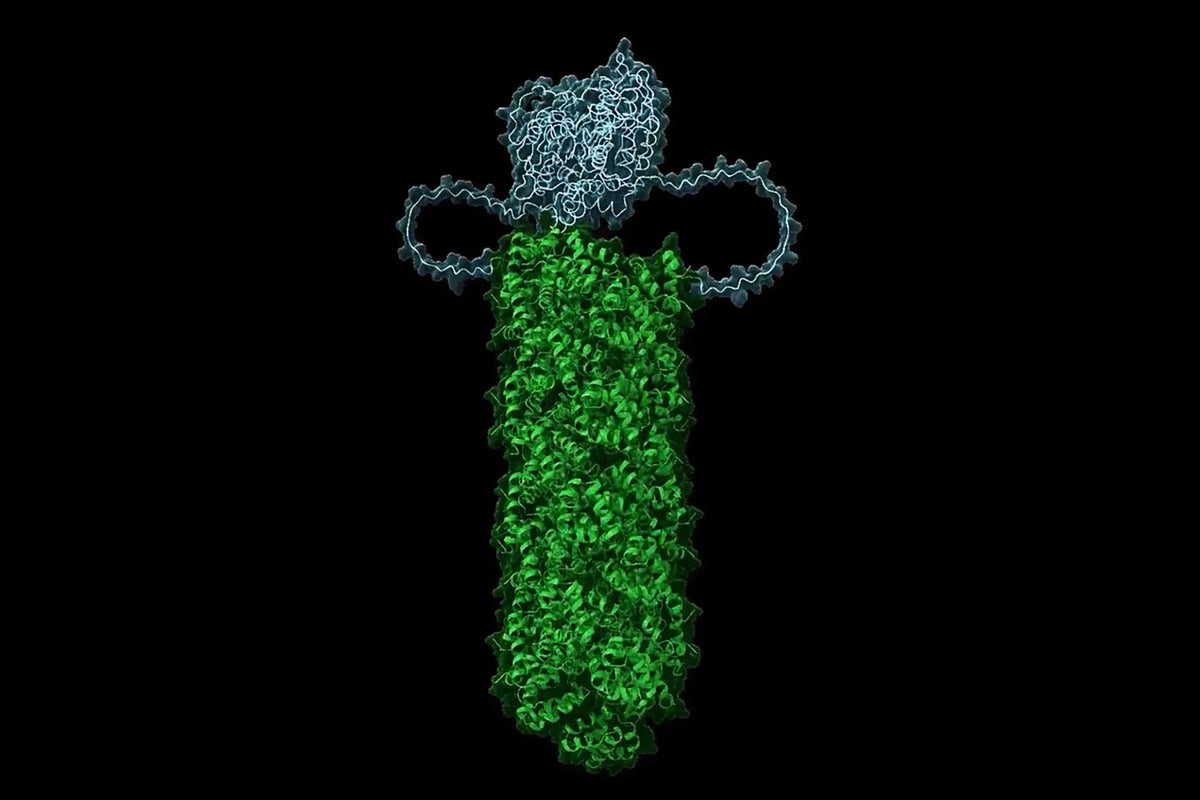

A team led by Randal Halfmann at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research has revealed that about 100 specialized immune proteins reside dormant inside every cell, waiting quietly for signs of viral invasion. When a virus infiltrates, it acts as a seed that triggers these proteins to clump together, forming a crystal-like scaffold. This scaffold then recruits enzymes called caspases, bringing them into close proximity with one another, which activates them to initiate a form of programmed cell death known as pyroptosis. Unlike apoptosis, which is a silent and orderly cell death, pyroptosis is inflammatory, signaling the immune system to respond to the infection aggressively.

Halfmann summarizes the finding poignantly: “The cells are literally waiting to die all the time.” This crystal-triggered cell death represents a highly sensitive and irreversible response, designed to outpace the virus’s ability to hijack the cell’s machinery. The proximity-induced activation of caspases is the key—it ensures that the cell only commits suicide when a sufficiently strong viral signal is present, avoiding unnecessary loss.

Traditionally, scientists have focused on understanding individual proteins by studying their folded structures in isolation. However, recent advances have shifted attention toward how proteins self-assemble into larger, membrane-less structures inside living cells, influencing cellular functions and decision-making processes. Molecular biologist D. Allan Drummond from the University of Chicago, who was not involved with the study, notes that this discovery contributes to a broader understanding of cellular organization, energy storage, and regulation beyond simple molecular interactions.

The study used both yeast cells and human cell lines to demonstrate this collective protein behavior. Typically, protein aggregates are associated with diseases such as Alzheimer’s, where misfolded proteins accumulate pathologically. However, this research highlights a contrasting role: solid protein clumps can serve critical, beneficial functions. In this immune context, the formation of a crystalline scaffold is an irreversible, spontaneous event that facilitates a rapid and decisive cellular response to viral threats. This mechanism enables the cell to “make decisions” that include self-destruction to protect the organism.

One remarkable aspect of this discovery is its speed. If the cell had to rely on slower genetic signaling pathways to respond to infection, viruses with rapid replication cycles could exploit the delay to take over the cell’s protein-making apparatus. The crystal-triggered clustering of immune proteins and caspases allows the cell to bypass such delays, committing quickly to pyroptosis before the virus can gain a foothold.

While previous studies had observed similar protein behaviors in test tubes, it was unclear whether such crystallization occurred naturally inside living cells. Bostjan Kobe, a protein structural biologist at the University of Queensland, highlights the significance of this research: “What was really lacking was, ‘Does this really happen in the cell?’ Halfmann’s work was really interesting because it came at the problem from a completely different angle.”

Interestingly, Halfmann’s team also found that these immune proteins can crystallize spontaneously over time, even in the absence of viral infection, leading to unintended cell death and inflammation. This spontaneous crystallization occurs at a low frequency but suggests that every cell has a ticking clock toward death via this mechanism. Other forms of cell death, such as apoptosis, may intervene first, but this finding underscores a fundamental trade-off between cellular longevity and immune readiness.

The researchers measured the tendency of these proteins to crystallize across various human cell types and discovered a correlation with cell turnover rates. Cells that are replaced frequently, such as certain blood cells, have higher concentrations of these immune proteins, while long-lived cells like neurons contain fewer. This suggests that spontaneous activation of this crystallization mechanism may contribute to the natural turnover of cells in the body.

Moreover, the study offers insights into the chronic, low-grade inflammation often observed with aging. As cells accumulate spontaneous crystallizations over time, they may trigger inflammatory responses that contribute to aging-related tissue damage. Preventing or